Duke Ellington is an interesting guy. I was aware of him as a suave, sophisticated bandleader, and he was this, but of course, not always. During the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and early 1930s, he was a young musician who hadn't quite found his groove, signature sound, and persona. Some of the polished tunes we know of as his were composed during that era but evolved as styles of music changed. But let me back up a bit...

Edward Kennedy Ellington was born in Washington, DC, in 1899. His father was a butler, and able to send Duke and his much-younger sister to good schools. (Later, when he found success, Ellington would bring his parents and sister to live with him at Sugar Hill in Harlem). The popular music of Ellington's teen years was ragtime, and those sounds drew him to the piano. He eventually formed a group with some musician friends and they found work playing "under-conversation" music for DC society parties. The group left Washington in 1919 to look for success in New York. They didn't find it, and so returned to DC for a few more years. In 1923, they went to New York as "The Washingtonians" (a seven-piece band) and found work playing at the Hollywood Club in Midtown. This is where they developed their style. They discarded the 'sweet' music of the posh DC parties and began playing wilder jazz sounds inspired by the bands in the Harlem clubs uptown. Also at this time, Duke was emerging as the leader of the band. They began to record in November 1924. Here's a sample of the primitive recording of that time--the band played into a megaphone-looking thing rather than into microphones.

The Washingtonians with Duke Ellington as their front man became very popular, and attracted the attention of Irving Mills, a music publisher who exploited composers by claiming songwriting credits which led to royalties on whatever sold. So on the one hand, Irving Mills took more than he was really entitled to, but on the other hand, he brought even more attention to Duke and the Washingtonians. The musicians up to this time had been operating with head arrangements, where they would gather around the piano and decide who would play what in performance. Duke insisted that they memorize their parts so that they would be aware of what was going on musically. When Irving Mills entered the picture and wanted sheet music to sell, those public-friendly arrangements had to be reconstructed because they never existed on paper in an organized fashion to begin with.

During this time, a trumpeter by the name of James "Bubber" Miley played with the band. His gimmick was to use the rubber part of a toilet plunger as a mute to create a 'growly' sound. He was mimicking King Oliver, a band leader from New Orleans and Chicago. This sound changed the character of the Washingtonians, especially when the other brass players mastered the technique. Bubber Miley quit the band in 1929 and died in 1932, so he never knew that his gimmick stayed with the band and became standard in jazz even now. Here is a short film showing another trumpeter, Arthur Whetsol, and Duke working out a head arrangement. Whetsol demonstrates the growly trumpet technique.

Here's something else you probably didn't know about early Duke Ellington compositions: while he and Irving Mills officially have the songwriting credits, many of those tunes came from the musicians in the band. Duke would hear a musician warming up or noodling around with a melody, and work that tune into an idea for the band without giving the musician credit. He never studied much harmony, musical form, or orchestration, so he composed in what Teachout describes as a 'mosaic' style: putting musical parts together without much transition or traditional form. Irving Mills came in and sometimes titled the piece (he claims that he titled "Mood Indigo"), and sometimes after the fact words would be added by a third party.

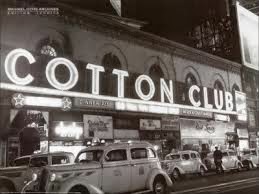

In 1927, the leader of the house band at the famous Cotton Club in Harlem died. Duke and his band got the job--they were already popular and had a following.

|

| The Cotton Club in Harlem |

That's where we'll leave Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. They are very popular at the Cotton Club in Harlem and about to embark on national and then European tours. Black musicians did not have an easy time finding hotel rooms at this time. They got around this in their American tours by sleeping in their own customized Pullman cars attached to regularly-scheduled trains. Duke Ellington and white Irving Mills protected the band members from prejudice so well that they didn't know the extent of what existed unless they left the band. They were extremely popular, now as Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra, continuing to polish their style into the 1930s, '40s, '50s, '60s, and even the early 1970s. They never lost their original signature tunes, but rearranged them constantly and added newer techniques.

By the way, while they were touring but still considered the house band at the Cotton Club, another band led by a guy named Cab Calloway took over at the club. But that's the subject of a future Harlem Renaissance-themed post...

No comments:

Post a Comment